A recent study by Cape Town scientists Dr Jo Barnes and Professor Leslie Petrik has triggered a dispute with the City of Cape Town over the quality of the city's coastal waters.

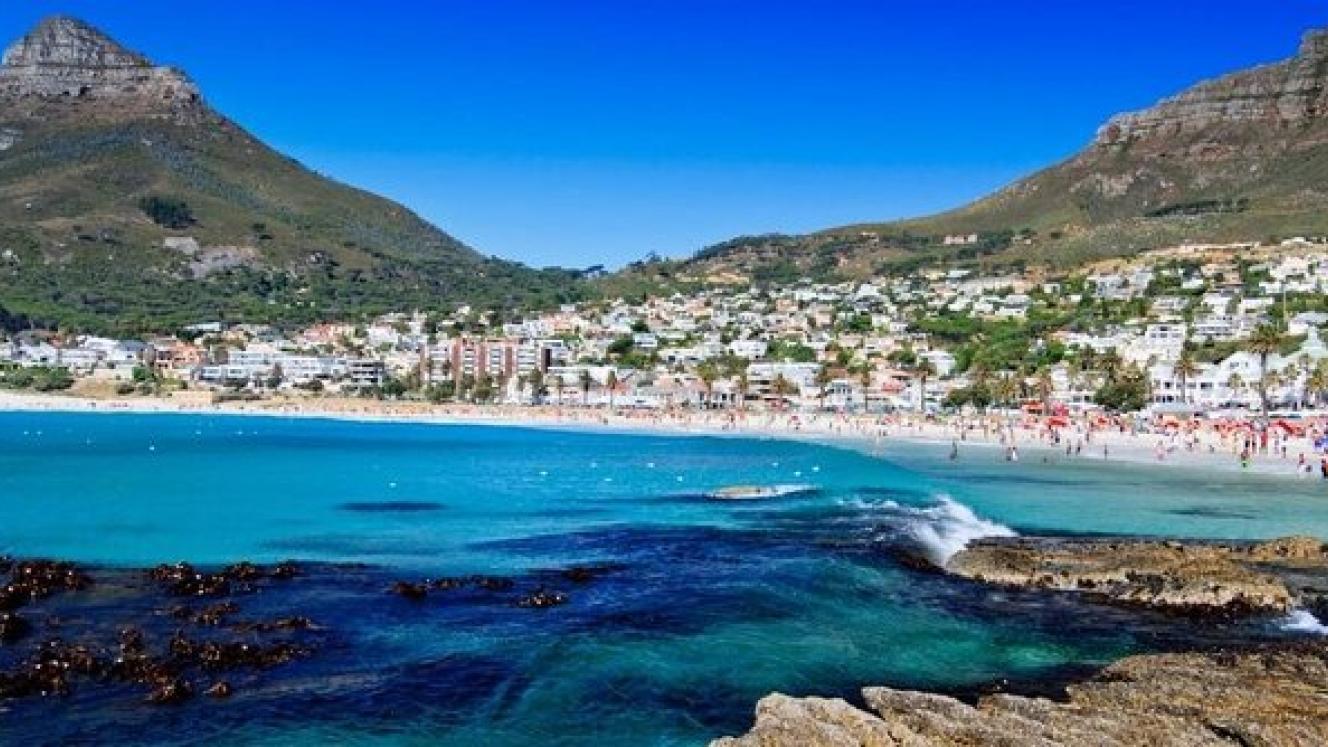

The controversy revolves around findings from Project Blue, a citizen-led pilot study conducted in November and December 2024. The study suggested potential sewage pollution at several beaches, including Camps Bay, Clifton and Strand.

Project Blue reported the presence of E.coli and enterococci in water samples, raising concerns about public health risks for beachgoers.

The researchers asserted that their methods adhered to international scientific standards, with sterilised sample collection, temperature-controlled transportation and prompt laboratory analysis within four hours. They aimed to offer a snapshot of water safety to inform swimmers.

Dr Barnes and Professor Petrik emphasised that their investigation was not intended as a comprehensive study but rather as a pilot project to highlight potential risks. However, their findings faced immediate pushback from the City of Cape Town.

The City’s Deputy Mayor and Mayoral Committee Member for Spatial Planning and Environment, Eddie Andrews, questioned the credibility of Project Blue’s findings.

According to Andrews, the City’s analysis, conducted by laboratories accredited by the South African National Accreditation System, consistently showed high water quality across 30 coastal recreational nodes during the festive season.

Of nearly 300 samples taken, 100% met recreational use thresholds based on enterococci levels, the globally accepted standard for assessing sewage pollution in marine waters.

Andrews criticised Project Blue’s inclusion of E.coli as a measure, citing international guidelines that deem it unsuitable for marine environments.

Furthermore, the City contested the accreditation of laboratories used by Project Blue, stating they were not certified for analysing enterococci or E.coli in seawater.

Andrews described the report as “limited and misleading,” suggesting it failed to cite robust scientific references and disproportionately focused on known pollution hotspots, such as Lagoon Beach in Milnerton.

Dr Barnes and Professor Petrik defended their findings, calling the City’s reaction “rather hysterical” and accusing officials of deflecting attention from underlying issues. They pointed to systemic challenges, such as failing sewerage systems and marine outfalls, which they believe contribute to ongoing pollution.

“This was a citizen science initiative meant to support public health,” said Petrik. “Instead of engaging constructively, the City is trying to shut down scientists.”

The researchers acknowledged the limited scope of their study but argued it highlighted critical issues warranting further investigation.

The City has launched a Summer Dashboard, providing weekly updates on enterococci levels at 30 popular beaches, aiming to reassure the public and promote informed decision-making.

Andrews emphasised that Cape Town’s extensive sampling efforts ensured a safe and enjoyable experience for beachgoers while promptly addressing pollution incidents.